"There are many ways to fight for peace, and there are many kinds of peace to fight for. There are those who try to prevent a battle from starting. There are those who, in the midst of battle, will seek to find ways to end the hostility. There are those who, after the fighting has ended, will fight popular opinion to honestly chronicle the events, giving all sides their say and perspective."

T. Jansen

|

| Osceola Seminole |

|

| Amiskquew |

History of the Indian Tribes of North America

By Thomas L McKenney and James Hall

|

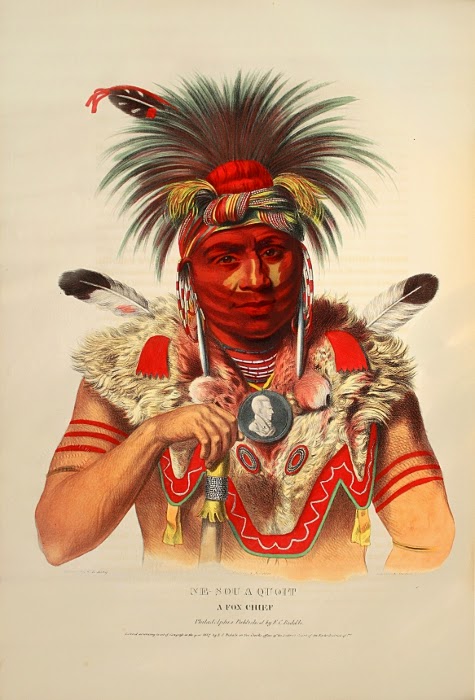

| Chief Ne-Sou-A-Quoit Fox |

|

| Chief Keokuk Sauk & Fox |

We all live among history, watching indifferently as it passes before our eyes, until one day, when it is too late, we realize that something of great value is gone forever. Regardless of what great things may have come to replace what has been lost, all progress comes at a cost. In the case of the Native American Indians, what was lost was not just land, but a way of life, and even life itself.

Thomas McKenney was born in 1785 in Hopewell, Maryland, and died in 1859 in New York City. As anyone who ever looked at the gravestone of a loved one can tell you, it’s not the dates on the stone that matter, but what happened in-between. McKenney served as the U.S. Superintendent of Indian Trade from 1816 to 1823, and then as the Head of the Office of Indian Affairs between the years 1824 and 1830. He served in these capacities under four presidents, starting with Madison, followed by Monroe, Adams, and Jackson. McKenney vigorously supported education of Native Americans, and was a firm believer that success could not be achieved without knowledge.

Thomas McKenney was born in 1785 in Hopewell, Maryland, and died in 1859 in New York City. As anyone who ever looked at the gravestone of a loved one can tell you, it’s not the dates on the stone that matter, but what happened in-between. McKenney served as the U.S. Superintendent of Indian Trade from 1816 to 1823, and then as the Head of the Office of Indian Affairs between the years 1824 and 1830. He served in these capacities under four presidents, starting with Madison, followed by Monroe, Adams, and Jackson. McKenney vigorously supported education of Native Americans, and was a firm believer that success could not be achieved without knowledge. |

| Chief Wapello Meskwaki |

Starting in 1816, McKenney used government funds to commission a series of oil paintings of the Native Americans who traveled to Washington, D.C. as delegates to negotiate treaties. His dream was to preserve, “in the archives of the Government whatever of the aboriginal man can be rescued from the destruction which awaits his race." He believed that American Indians should be "looked upon as human beings, having bodies and souls like ours, possessed of sensibilities and capacities as keen and large as ours, that their misery be inspected and held up to the view of our citizens, that their trophies of reform be pointed to. I say, it needs only this to enlist into their favor the whole civilized population of our country".

The artist who produced most of these paintings was Charles Bird King. It was always McKenney’s intention to publish reproductions of the paintings in book form, and to that end he found a partner in Samuel F. Bradford. In 1830, McKenney and Bradford announced plans for the portfolio, which they heralded as “a great, national work”, but soon afterwards McKenney was fired from his government position in Jackson’s administration. Undaunted, he moved to Philadelphia and proceeded with the project.

The artist who produced most of these paintings was Charles Bird King. It was always McKenney’s intention to publish reproductions of the paintings in book form, and to that end he found a partner in Samuel F. Bradford. In 1830, McKenney and Bradford announced plans for the portfolio, which they heralded as “a great, national work”, but soon afterwards McKenney was fired from his government position in Jackson’s administration. Undaunted, he moved to Philadelphia and proceeded with the project.The publishing history of the portfolio is incredibly complicated. McKenney’s first contract was with the lithography firm of Childs and Inman of Philadelphia. McKenney obtained access to the portraits in the gallery, having them carried by hand or shipped one by one to Philadelphia, and he shrewdly had Inman copy in oil each Indian portrait as it arrived from Washington, so that the lithographs could be made later. But progress was slow, and after four years only a dozen portraits had been lithographed and his partner, Bradford, was bankrupt. Two young Philadelphia printers, Biddle and Key, bought Bradford out.

|

| Chief Tuko-See-Mathla Seminole |

Over the next five years a number of lithographers—Childs, Inman, Lehman and Duval, in various partnerships—continued the work on the portfolio, and in February 1837 the first volume was published, a culmination of eight years of effort. The book met great success, subscriptions swelled, but Lehman and Duval withdrew from the enterprise in August 1837. They were replaced by J. T. Bowen of New York, “who worked on a far grander scale than the previous lithographers.” Bowen immediately transferred his business to Philadelphia. Up to this point no fewer than four combinations of partners had worked on the lithographs, and the first volume of the work (containing a total of 48 plates) was a mix of plates produced by these firms under several publishers.

|

| Chief McIntosh |

With his finances in tatters, and his beloved Portfolio in jeopardy, McKenney attempted to remain solvent through speaking engagements and the publication of his memoirs. He struggled to keep the Portfolio in print, but the struggle took its toll. McKenney was forced to officially withdraw from the project late in 1837.

It was at this point that James Hall picked up the entire work, intent on completing the project himself. Hall continued to work for many years, tracking down and recording the histories of the Indians portrayed in the spectacular oil paintings, which were still housed in the War Office at that time. In 1841, Biddle and Bowen transferred the publication rights to the firm of Rice and Clark, the assignees of the now bankrupt Greenough, which became the fifth and final publishers of the portfolio.

The second volume of the series was published in 1842, and the third and final volume was published in 1844. The three-volume set, titled History of the Indian Tribes of North America, is now one of the most valued items of Americana, usually found only in rare book rooms of libraries and museums. Author James Horan described the series in his 1988 work, The McKenney-Hall Portrait Gallery of American Indians by saying, “The value of this magnificent work is chiefly in its faithful recording of the feature and dress of celebrated American Indians who lived and died long before the age of photography."

McKenney continued to champion the cause of the American Indians, even after withdrawing from the series. He allocated a portion of his speaking funds to poverty-stricken tribes. In February 1859, Thomas McKenney died, not knowing that his life's work would eventually stand as one of the major American publications of the nineteenth century.

|

| Chief Ledasie Creek |

It is fortunate that McKenney and Hall put so much of their time and effort into preserving both the paintings, which were McKenney’s brainchild from the first, and the histories of the Native American subjects of those paintings. In 1858 the original oil paintings were transferred to the first Smithsonian Institute building known as ‘The Castle’. In 1865, workers in the building who were moving the paintings from one location to another accidentally set the building on fire, and all but five of the 300 paintings were destroyed.

|

| Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak Black Sparrow Hawk (aka Black Hawk) Sauk Warrior and Leader |

(Key Terms: Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, Black Sparrow Hawk, Black Hawk, 1767, Saukenuk, Pyesa, Rock Island, Black Hawk’s Watch Tower, Black Hawk State Historic Site, Hauberg Museum, Sauk, Sac, Meskwaki, Fox, Rock River, Sinnissippi River, Mississippi River, War of 1812, British Band, Great Britain, Treaty of 1804, Treaties, Ceded Land, William Henry Harrison, Quashquame, Keokuk, Fort Armstrong, Samuel Whiteside, Black Hawk War of 1832, Black Hawk Conflict, Scalp, Great Sauk Trail, Black Hawk Trail, Prophetstown, Wabokieshiek, White Cloud, The Winnebago Prophet, Ne-o-po-pe, Dixon’s Ferry, Isaiah Stillman, The Battle of Stillman’s Run, Old Man’s Creek, Sycamore Creek, Abraham Lincoln, Chief Shabbona, Felix St. Vrain, Lake Koshkonong, Fort Koshkonong, Fort Atkinson, Henry Atkinson, Andrew Jackson, Lewis Cass, Winfield Scott, Chief Black Wolf, Henry Dodge, James Henry, White Crow, Rock River Rapids, The Four Lakes, Battle of Wisconsin Heights, Benjamin Franklin Smith, Wisconsin River, Kickapoo River, Soldier’s Grove, Steamboat Warrior, Steamship Warrior, Fort Crawford, Battle of Bad Axe, Bad Axe Massacre, Joseph M. Street, Antoine LeClaire, Native American, Indian, Michigan Territory, Indiana Territory, Louisiana Territory, Osage, Souix, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Ho-Chunk)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.