Arrival at Saukenuk

February 14, 2014

Black Hawk State Historic Site

Rock Island, IL

|

| Watch Tower Bluff - overlooking Rock River Rock Island IL |

Frigid wind blows through naked tree branches high on the bluff. The setting sun lies unseen behind a grey veil of clouds, hovering in unbroken dominance over the snow-covered earth.

|

| Current South-facing view from Watch Tower Bluff Black Hawk State Historic Site Rock Island IL |

Across the Rock River, to the south, is an unsightly rock quarry, with its towering machinery and piles of unsettled earth and stone. The eye is drawn to its ugliness, unable to look above or beyond, like witnessing an unavoidable automobile accident just before it happens.

|

| Black Hawk's South-facing View from Watch Tower Bluff Saukenuk |

Standing on this bluff, in cold, stony effigy, is a statue of Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak. His unblinking stone eyes gaze from atop this bluff, his favorite spot to be alone, this bluff that now bears the name ‘Black Hawk’s Watch Tower’, remains transfixed just as it was in life, staring bleakly at a future he knew had changed forever. Here he stands, in front of the now historical building called Watch Tower Lodge, wrapped in his hide leggings and woolen blanket, his bald head decorated with eagle feathers, all made of stone. Visitors to the Lodge stand and stare at the statue, sitting high atop a large, granite pedestal. The monument, for indeed this is a tribute to the man, simply says ‘Blackhawk’, in bold, capital letters. It is the central figure in the courtyard, standing alone in a place of prominence, remembered, but not truly remembered.

Standing on this bluff, in cold, stony effigy, is a statue of Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak. His unblinking stone eyes gaze from atop this bluff, his favorite spot to be alone, this bluff that now bears the name ‘Black Hawk’s Watch Tower’, remains transfixed just as it was in life, staring bleakly at a future he knew had changed forever. Here he stands, in front of the now historical building called Watch Tower Lodge, wrapped in his hide leggings and woolen blanket, his bald head decorated with eagle feathers, all made of stone. Visitors to the Lodge stand and stare at the statue, sitting high atop a large, granite pedestal. The monument, for indeed this is a tribute to the man, simply says ‘Blackhawk’, in bold, capital letters. It is the central figure in the courtyard, standing alone in a place of prominence, remembered, but not truly remembered.Inside the stone building, with the stone roof, in the Hauberg Indian Museum, is a series of life-size dioramas and artifacts depicting life in the village of Saukenuk, and telling some small part of the history of the man and his people. A visitor to the museum can speak to a staff member sitting at the front desk, receive some literature, ask about the displays, and perhaps be encouraged to leave a small, suggested donation to maintain the artifacts. But not at night. The museum keeps modest hours, to match the modest staffing.

On this night, February 14th of 2014, the Lodge is host to its annual Valentine’s Day Contra Dance and Moonlight Walk. The mood inside is festive – friends and families packed wall-to-wall eating fresh donuts, drinking cider and hot chocolate, and listening to the live-band hootenanny of blue grass and Appalachian Stomp music. I walked among this crowd, ate the food, drank the cider, and even danced to the music, but was never really part of the event. I had come hundreds of miles to stand in front of the building and stare at the statue out front, to contemplate Black Hawk’s life, to contemplate his death, to understand what he may have been thinking, to listen to his spirit talking in the trees, to open my heart to the land of the people and feel what they felt, to stare out from the top of Black Hawk’s Watch Tower and see what he had seen 200 years ago. I came to be with Black Hawk the man, Black Hawk the spirit. I came to breathe the air he breathed, to look with my own eyes upon trees, still alive, which were saplings when he lived here. I came to see the mighty Mississippi and the comely Sinnissippi, to look out upon the islands, to see the birds, the deer, the oaks and the sycamores. I came to follow the great leader. To travel with the spirits of his fated band as they walked peacefully into hatred, as they defended themselves against attack, as they retaliated to survive, as they outwitted a legion of men who followed them, intent on killing and retribution, as they fought, and split up, and hoped, and struggled, and dwindled, and starved, and fought again, and suffered a final, unspeakable defeat. I came to walk the path of a story I had come to know through the words of both white people and Indian people. I came to listen to the earth retell the story, to hear the knocking of the woodpeckers, to see Bufflehead ducks filling the un-frozen river as it flowed past desolate, sandy banks.

|

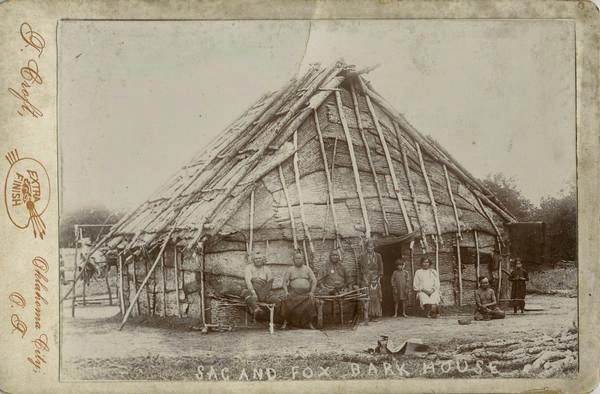

| Sac and Fox Bark House |

(Key Terms: Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, Black Sparrow Hawk, Black Hawk, 1767, Saukenuk, Pyesa, Rock Island, Black Hawk’s Watch Tower, Black Hawk State Historic Site, Hauberg Museum, Sauk, Sac, Meskwaki, Fox, Rock River, Sinnissippi River, Mississippi River, War of 1812, British Band, Great Britain, Treaty of 1804, Treaties, Ceded Land, William Henry Harrison, Quashquame, Keokuk, Fort Armstrong, Samuel Whiteside, Black Hawk War of 1832, Black Hawk Conflict, Scalp, Great Sauk Trail, Black Hawk Trail, Prophetstown, Wabokieshiek, White Cloud, The Winnebago Prophet, Ne-o-po-pe, Dixon’s Ferry, Isaiah Stillman, The Battle of Stillman’s Run, Old Man’s Creek, Sycamore Creek, Abraham Lincoln, Chief Shabbona, Felix St. Vrain, Lake Koshkonong, Fort Koshkonong, Fort Atkinson, Henry Atkinson, Andrew Jackson, Lewis Cass, Winfield Scott, Chief Black Wolf, Henry Dodge, James Henry, White Crow, Rock River Rapids, The Four Lakes, Battle of Wisconsin Heights, Benjamin Franklin Smith, Wisconsin River, Kickapoo River, Soldier’s Grove, Steamboat Warrior, Steamship Warrior, Fort Crawford, Battle of Bad Axe, Bad Axe Massacre, Joseph M. Street, Antoine LeClaire, Native American, Indian, Michigan Territory, Indiana Territory, Louisiana Territory, Osage, Souix, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Ho-Chunk)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.