As the Black Hawk Conflict progressed, factions of other tribes joined or tried to join Black Hawk. Amidst the chaos of war, other Native Americans and settlers carried out acts of violence for personal reasons. In one example, a band of Ho-Chunk intent on joining Black Hawk's Band attacked and killed the party of Felix St. Vrain in what Americans knew as the St. Vrain massacre. This act was an exception as most Ho-Chunk sided with the United States during the Black Hawk Conflict. The warriors who attacked St. Vrain's party had acted independently of the Ho-Chunk nation. From April to August, Potawatomi warriors also joined with Black Hawk's Band.

No full account of the actual path followed by Black Hawk and his band exists, and certainly they did not travel as a single, undivided mass up the Sinnissippi. Running for their lives, they nonetheless had to forage for food and evade the trailing troops for their very survival. Many accounts describe feints by the warriors intended to draw the troops away from the main body of the band. Black Hawk sent many small scouting parties in many directions seeking aid from other Indian tribes, and looking for a place where safety could be found, a new home established, and preparations made for the upcoming winter. More than once, soldiers would track and follow signs left behind by the Sauk, only to find nothing at the end of the trail. “Like tracking a shadow” wrote one soldier, in describing their attempts to even find Black Hawk and his people, let alone engage them in battle.

Many conflicts erupted in what is now northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin, while an inept and ill-informed military scoured the wilderness looking for a fight, and while fleeing Sauk and Potawatomi staged raids to steal supplies. Not all the skirmishes involved the Sauk Indians, but all were attributed to Black Hawk and his ‘British Band’ of warriors. Finally, on June 16th, soldiers confronted a group of Kickapoo warriors near a small oxbow bend in the Pecatonica River near present-day Woodford Wisconsin. This battle became known as the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Though nowhere near Black Hawk and his band, it was nonetheless a victory for the militia as eleven Indians were killed compared to only three soldiers. Two days later, a small group of Black Hawk's Sauk warriors were engaged and defeated at Yellow Creek, near what is now Waddam’s Grove Illinois. Spurred on by word of the victories, the militia surged on with renewed fervor, bent on destroying Black Hawk and all his band.

Black Hawk himself, and a vastly reduced number of the people who initially crossed the Mississippi with him, continued northeast along the Sinnissippi, eventually stopping and camping in a marshy area on the north end of Lake Koshkonong. This became a base of operations for the band, and a safe haven for the women, children and elderly. No longer restricted by a restraint of violence, Black Hawk and his warriors, along with Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi warriors began leading raids against the white settlers to capture provisions. Not all Native Americans in the region supported this turn of events; most notably, Potawatomi chief Shabonna rode throughout the settlements, warning whites of the impending attacks.

The campsite was located within four miles of Fort Koshkonong, later renamed Fort Atkinson, after General Henry Atkinson, the very person leading the military force charged with finding and subduing Black Hawk. It is unknown if Atkinson was unaware of the large band of Indians camped so near his base, or if their character was so dissimilar to the “2000 bloodthirsty warriors … sweeping all Northern Illinois with the bosom of destruction" described by Stillman after his humiliating defeat that he simply couldn’t recognize them as his long-sought enemy, but Black Hawk and his band were able to remain for a period of weeks hiding in plain sight.

Even with the raided provisions, there was never enough to sustain such a large group who could not openly hunt and gather needed food and supplies. Many left to seek help, attempt to return to Iowa, or to simply go their own way. Many were sick or dying. All were weak with hunger. By now it was clear that there would be no help from the British, no stores of weapons, no offer of food and winter accommodations from the Ho-Chunk or the Potawatomi.

|

| Henry Atkinson |

|

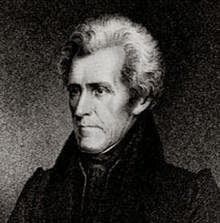

| Andrew Jackson |

|

| Lewis Cass |

At first, when Black Hawk learned of the new and massive force being raised against him, he sent out raiding parties far to the west, in an effort to draw troops away from his Lake Koshkonong base. He himself took part in a raid all the way down near present-day Elizabeth, Illinois on June 24th, and the following day led a successful battle against Major John Dement and his troops back in Kellogg’s grove. It would be his last victory in the conflict, though not yet his last or greatest achievement.

From Koshkonong, Black Hawk led his band north, up the Sinnissippi to what is now Watertown, then pushed on nearly all the way to the great rapids located on the south end of Lake Sinnissippi, near present day Hustisford. About a half-dozen miles short of the rapids, Black Hawk discovered confrontation with the militia was imminent, and in fact, it was here that two or three days later, Little Thunder, a Winnebago guide assisting the militia, found fresh trail left by the refugees.

After consulting with his Winnebago guide, Black Hawk formulated a new plan to escape to the west, across Michigan Territory (Lower Wisconsin) to the Mississippi River. With help from Chief Black Wolf, who acted as his guide through the marshes and wetlands of the territory, Black Hawk fled to the west.

Earlier that month, on June 15th, President Andrew Jackson appointed General Winfield Scott as the new commander of the American Forces in the conflict, having grown displeased at Atkinson’s inept handling of the war effort. Scott gathered a force of approximately 950 soldiers and departed from Buffalo, New York by steamship, just as a Cholera epidemic was sweeping the East Coast. Many of his men sickened and died, and many more were released or deserted at each stop along the way to Chicago. At the end of July, Scott raced west ahead of his 350 remaining troops intent on taking command of the existing forces and waging a final, decisive campaign against Black Hawk’s warriors. Neither he nor his 350 men would ever see battle.

(Key Terms: Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, Black Sparrow Hawk, Black Hawk, 1767, Saukenuk, Pyesa, Rock Island, Black Hawk’s Watch Tower, Black Hawk State Historic Site, Hauberg Museum, Sauk, Sac, Meskwaki, Fox, Rock River, Sinnissippi River, Mississippi River, War of 1812, British Band, Great Britain, Treaty of 1804, Treaties, Ceded Land, William Henry Harrison, Quashquame, Keokuk, Fort Armstrong, Samuel Whiteside, Black Hawk War of 1832, Black Hawk Conflict, Scalp, Great Sauk Trail, Black Hawk Trail, Prophetstown, Wabokieshiek, White Cloud, The Winnebago Prophet, Ne-o-po-pe, Dixon’s Ferry, Isaiah Stillman, The Battle of Stillman’s Run, Old Man’s Creek, Sycamore Creek, Abraham Lincoln, Chief Shabbona, Felix St. Vrain, Lake Koshkonong, Fort Koshkonong, Fort Atkinson, Henry Atkinson, Andrew Jackson, Lewis Cass, Winfield Scott, Chief Black Wolf, Henry Dodge, James Henry, White Crow, Rock River Rapids, The Four Lakes, Battle of Wisconsin Heights, Benjamin Franklin Smith, Wisconsin River, Kickapoo River, Soldier’s Grove, Steamboat Warrior, Steamship Warrior, Fort Crawford, Battle of Bad Axe, Bad Axe Massacre, Joseph M. Street, Antoine LeClaire, Native American, Indian, Michigan Territory, Indiana Territory, Louisiana Territory, Osage, Souix, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Ho-Chunk)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.