April 13, 2014

Wisconsin Heights Battle Site

Roxbury, WI

I feel it is important to reintroduce myself, and talk about the purpose of this web log. My name is Theresa Jansen, and I am descended from an Ojibwe Native American, though my grandmother's name and the tribe of my ancestry, has been lost to me. I am in the process of taking a journey, both spiritual and physical, following the path taken by the Sauk warrior Makataimeshekiakiak, also known as Black Sparrow Hawk, leader of the native people caught up in the conflict known as ‘The Black Hawk War’ of 1832. The story is at once both tragic and inspiring, but above all, shameful to those of us who think of ourselves as proud Americans living in a land of freedom, individual rights, equality, and justice.

It is here, nestled in the hills of the Mazomanie Oak Barrens State Natural Area just south of Sauk City, Wisconsin, that I first engaged the trail of Black Hawk and his band. Why here? Well, there is a lot to that story. Believe me when I tell you this blog isn't even the half of it.

I will, as with my other posts, tell you about my visits to this location, and recount the story of Black Hawk and his people as they passed through. I will talk about their pursuers, the militia forces led by commanders Dodge and Henry. I will give you my thoughts and reactions, and lastly my prayers, but first I will try to explain again how this all came about.

I have finally reached the part of my journey where it began, so to speak. As I already stated in my post Following Black Hawk’s Trail, I have spent all my life in Wisconsin, and have felt drawn to this particular area of the state for many reasons. (If you have not read that post, I encourage you to do so now, and then return to finish reading this one.) As a child, my family would take trips driving through this region, and my father would tell us stories about our ancestors, who had lived in the area - a great-great uncle here, or a great grandfather there. I was young, and I didn't listen closely enough while I had the chance. Now, I must undertake the journey without him. The folly of youth, the wisdom of years, a moment of pride, a lifetime of tears.

The stories I did listen to, however, were about my Native American grandmother. I have spent long hours pursuing documents through dusty archives, church basements, and online vaults, visiting cemeteries, and asking family members what they know or remember. I have had DNA testing performed, to verify my Native American heritage, and ordered countless documents from vital records departments. More than once I have despaired at the difficulty of finding documented information about my Indian ancestry, so that I might know my Indian grandmother's name, tribal affiliation, and clan. Nevertheless, I keep digging.

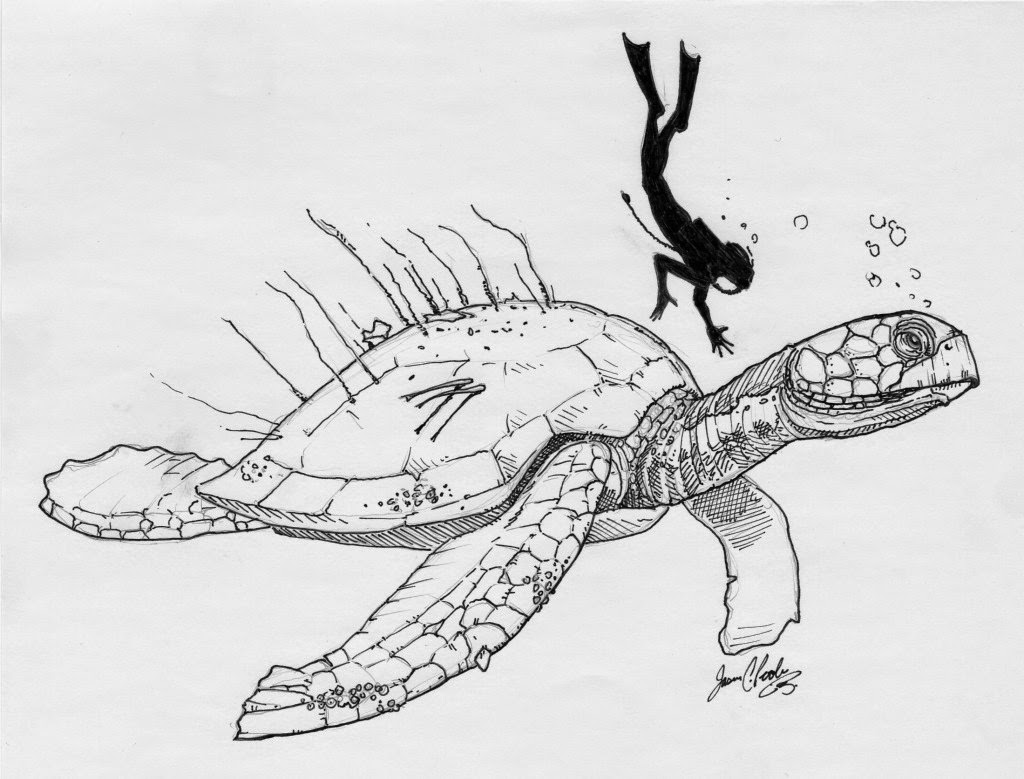

I recently read the story of a fossilized turtle bone, which was from the upper right flipper of an Atlantochelys Mortoni. In 1849, the naturalist Louis Agassiz found a broken piece of bone which he identified as a unique species, some 75 million years old. No complete skeleton of one of these massive, extinct sea turtles has ever been found. In fact, no other bones have ever been found which could clearly be identified as belonging to the mysterious giant – until now. In 2012 an avocational paleontologist by the name of Gregory Harpel was rooting around the Monmouth Brooks region of New Jersey and happened across a fossilized bone. He took it to an expert who recognized it as belonging to a very large turtle, and then laughingly remarked that it might even be the long-lost missing half of the bone discovered by Agassiz 163 years earlier. Of course, what made this story so fantastic was that the two halves of the bone did indeed fit together – a perfect and undeniable match. By finding the second half of the only known bone in existence for this species of animal, it was now possible to calculate the approximate size of the turtle – an astonishing 10 feet, making it one of the largest known species of turtle – which was not possible to any certain degree with only half a bone.

I tell this story not just because it is fascinating to me, but because it demonstrates how people, events, and even things that are separated by dozens or hundreds of years can suddenly merge together to form a complete and compelling story.

My story is not so spectacular, but it is similar in nature. While living in the Cross Plains area, in the early 1980's, I was overwhelmed by the sense that a great battle had taken place nearby, and that many Indians had been killed. I asked around, but no one was able to remember any battles that had taken place in or around Cross Plains. Somebody thought there had been a fight between some soldiers and some Blackhawk Indians and maybe some Kickapoo Indians a long time ago, but they didn't know anything else about it.

Decades later, a friend of mine, Joni, after hearing some of my stories, said that the event sounded a lot like the Battle of Wisconsin Heights, so she sent me a hyperlink to some historical archives.

Like a Jules Verne traveler, I felt like I was caught in the outer edge of a vast temporal vortex whose center was the two large hills near the banks of the Wisconsin River where this battle was fought. I learned, to my utter shock, that the battle had taken place on land that was once owned by my Great, Great, Great Grandfather, Kaspar Hornung. More, I discovered that this was the branch of the family tree from which my Native American ancestry originated. Suddenly the random puzzle pieces started to form a picture. I felt a sensation not unlike vertigo.

| Hornung Homestead Site of Battle of Wisconsin Heights (Black Hawk Mound in background) |

I traveled to this piece of land, and discovered the original family homestead, with one of the early homes still standing. My ancestor did not immigrate to this country until 1846, and therefore, did not participate in the 1832 conflict, but he, Kaspar, was the first white settler to build and farm on this bloodied battleground.

The more I learned about the Battle of Wisconsin Heights and Black Hawk himself, the more intrigued I became with his story. I came seeking a connection to my genealogical roots, and I discovered a story so compelling and so completely in touch with that invisible yearning in my soul that I immediately undertook the mission to pursue the history and publish this story in a way that connected the loose fragments of my life, discovered through time, into a new and more complete narrative.

I do not pretend to be telling a story that has not been written before, nor do I believe that I hold some vital clue which now makes it possible for a great advancement in historical knowledge and perspective. Indeed, there are an incredible number of books, articles, museums, statues, memorials and other websites that hold an astonishing amount of detail about Black Hawk’s fated journey. It is my hope, however that in this web log the story is told in a way that no one else has told it, and perhaps I have added one or two new pieces to the whole.

I have visited the site of the battle many times over the past year. While seeking to learn more about my Indian heritage, and to practice some of the spiritual ceremonies I have been learning from my Native American friends. I came to this land to commune with the people who died here, to remember them, honor them, and give them offerings of food and tobacco. While my German ancestors were not directly responsible for driving Black Hawk's people from these hills, I have come to realize that their very presence here contributed to the downfall of the indigenous societies in this area. My European ancestors and others like them saw nothing but an unclaimed land that was their's for the taking. Relentless greed and consumption created an unstoppable force that swept the Native Americans from their homes. It is no different than the melting of the polar ice caps. We all see it happening. We all know it’s bad. We all know it will ultimately lead to the destruction of much of our earth. We all sit quietly and wish it could be different. We all keep doing all the things we have always done that created the problem in the first place.

On one of my visits to the battle site, I brought my family with me, four generations of cousins who share German/Native American ancestry. We walked the trails up to the effigy mounds. We talked about Kaspars’s farm. We also talked about the battle, and the people who died here. I know the names of only two of the people actually buried on the site. The first is Mary (Hornung) Hackett, a young girl who was buried here long after the battle took place. The second is Thomas Jefferson Short, the only white casualty of the battle, buried on the same knoll as Mary, though I do not know for certain which knoll. There are Indians buried here as well. The burial mounds can still be visited today by walking a short trail up the hill from the parking lot on Hwy 78. (If you visit this site, please show respect or our Native American brothers and sisters, and do not walk on the top of the mounds.) The mounds are said to be over a thousand years old. I have been unable to confirm the accuracy of this assertion, since the historian at the Sac and Fox Nation does not know whether these mounds are Ho-Chunk or Sac. As to what became of the bodies of the estimated sixty-eight Indians who died here that soggy day in July, 1832, nothing is certain, except to say that at least 35 were scalped by the white soldiers and the Winnebago Indians who had been fighting alongside them. Colonel Dodge also stated that the Sauk were seen carrying the bodies of the fallen away from the battlefield, and some accounts have suggested that the dead were released to the great river to carry them downstream, back to the land of their birth.

On another one of my visits, I was joined by Joni and my husband, who walked with me from the edge of the Wisconsin River back to the battle site. At the river, we sang to the water and to the spirits of the people, telling them we were here to remember their bravery and their sacrifice. As we walked, we talked about the journey I was planning, but had not yet started in earnest.

Other times I came just by myself. I walked the land, and made small fires for meditation and healing. I spoke to the spirits and I prayed for them. I prayed that they would be able to let go of their anger, it was bad for their spirits, it was bad for the land. I asked them to follow the smoke from my fire and find contentment and joy in the land of the spirits. I spoke gently, telling them it was time for them to find peace. This land became the center of my journey. A seed grew within me here. On this land I found my Grandmother. On this land I found myself and the fruit of that vine is written on the pages of this blog.

***********************************************************************************************

When I arrived at the battle site today, it was raining steadily, just as it had been in 1832. I parked by the Historical Marker, which gives a more-or-less accurate summary of the events. The marker reads:

“On July 21, 1832, during a persistent rainstorm, the 65-year old Sac Indian leader, Black Hawk, led 60 of his Sac and Fox and Kickapoo warriors in a holding action against 700 United States militia at this location. The conflict, known as the Battle of Wisconsin Heights, was the turning point in the Black Hawk War. Here commanders General James D. Henry and Colonel Henry Dodge and their troops over-took Black Hawk and his followers after pursuing them for weeks over the marshy areas and rough terrain of south central Wisconsin. Yet because of Black Hawk's superb military strategy, the steady rain, and nightfall, approximately 700 Indians, including children and the aged, escaped down or across the Wisconsin River about one mile west of here. Their success was short-lived. The war ended just 12 days later at the Battle of Bad Axe when many of Black Hawk's followers drowned or were slain in their attempt to cross the Mississippi River.”

The fighting started at approximately three o’clock in the afternoon, when the troops finally caught up to some of Black Hawk’s warriors. Several small skirmishes and feints broke out, and the soldiers kept advancing after each. By five o’clock, the battle started in earnest. In his autobiography, Black Hawk states:

“Ne-a-pope, with a party of twenty, remained in our rear, to watch for the enemy whilst we were proceeding to the Ouisconsin, with our women and children. We arrived, and had commenced crossing them to an island, when we discovered a large body of the enemy coming towards us. We were now compelled to fight, or sacrifice our wives and children to the fury of the whites! I met them with fifty warriors (having left the balance to assist our women and children in crossing), about a mile from the river when an attack immediately commenced.”Black Hawk goes on to state:

“I would not have fought there, but to gain time for my women and children to cross to an island. A warrior will duly appreciate the embarrassments I labored under – and whatever may be the sentiments of the white people, in relation to this battle, my nation, though fallen, will award to me the reputation of a great brave in conducting it.”

I am fascinated by many things. Foremost is the observation that Black Hawk immediately recognized that despite the loss of life, and the eventual rout by the soldiers in forcing them from their position, this was a truly remarkable victory on the part of the Sauk warriors. Whether it was fifty warriors, as Black Hawk suggests, or even a hundred, he was vastly outnumbered by the more than 700 soldiers aligned against him. Yet somehow he managed to defend territory for over an hour and achieve his goal of enabling his people to escape. As he predicted, the white soldiers who fought there considered it a major victory themselves, because the loss of life was so dramatically one-sided, with only one soldier killed and eight wounded, compared to sixty or more Indians killed. Those who have studied the battle in retrospect, however, have great admiration for the strategy and tactics Black Hawk used in commanding his forces.

Another thing that fascinates me is how little space Black Hawk affords to his recollection of the battle. In one sentence, he passes from taking a position high on the hill, to have an advantage over the whites, to, “But the enemy succeeded in gaining this point, which compelled us to fall back into a deep ravine, from which we continued firing at them and they at us, until it began to grow dark.” The entire battle was told in two sentences. As dusk fell, he gave the order to his warriors to disburse and meet back at the Wisconsin River, by different routes, where he was “astonished to find that the enemy were not disposed to pursue us.”

This is in great contrast to the volumes and pages of material that were written by the soldiers and their commanders on the same subject. They go into great and painstaking detail to describe who was fore and who was in the rear, who was left and who was right, who shot and who got shot, where they were at the moment of the charge, where the horses were kept, and what orders were given by whom. Paintings have been made of the battle site. Maps have been drawn and published. Detailed charts of command have been rendered, and newspaper articles written commemorating the event. Nearly two hundred years later it is possible to study nearly every detail of the fighting, to the degree that one can stand with great certainly in the place where each squadron held their positions, and picture with ease the various attacks and retreats. To Black Hawk, this was just another skirmish in his long and storied military history. To the soldiers, it was finally the fight they had been seeking for months, and they wanted to record every last detail for posterity.

The entire battle at the site is said to have lasted approximately an hour and a half, through cold rain and an easterly wind, with low, heavy clouds and falling temperatures. Sunset would have been about 7:30 pm (daylight savings time was not observed in those days), and dusk would have been greatly hastened by the imposing weather. The consensus is that hostilities ended at approximately 7 pm. After days of marching through the most hostile of environments, and being deluged with rain, neither camp was willing to continue the battle into the evening, though both anticipated a nighttime raid.

As darkness fell, Black Hawk and what remained of his warriors crossed the Wisconsin River to rejoin their families. They were far fewer than before, but they had escaped the wrath of their pursuers. Black Hawk had lived to fight another day.

As-she-we-qua – today I call to your spirit and remember you as you waited in fear for the return of your husband, Makataimeshekiakiak. How terrified you must have been watching him ride away from the banks of the river to face an enemy who had chased you beyond reason across the vast wilderness, so far from your home. I picture you clutching your starving children to your breast, saying prayers to the Great Spirit asking for his safe return. I picture you standing strong – a leader among the women of the band, helping to build the rafts and canoes that carried people across the great river. I picture you crushing acorns, digging roots and barking trees to make what food you could for yourself and those around you, not even able to make fires in the drenching, cold rain, as darkness approached and you could hear the tremendous thunder of musket-fire in the near distance. I imagine your great, aching terror when the gunfire stops, and warriors don't return. I picture you sick with grief and hunger, torn as the minutes stretch by like hours until finally, against all hope, you see your husband returning to you across the river, his magnificent horse dying from battle wounds. I feel the swirling emotion in your heart, so happy that Black Hawk has come back to you, and so anguished that so many others did not return, leaving behind wives and children who are now broken beyond despair. I hear the silence and all that is said without words as he gazes at you with those dark, sad eyes on a face blackened with battle. I sense your fears and your doubts as you huddle together to keep warm, curled up in the wet grasses while sleep refuses to come. I am sorry, Singing Bird. I am sorry you had to suffer through this terrible day. I am sorry for all the women of your band who had no one to hold but each other on that cold, rainy night. I am sorry for your hunger and your pain, though I am glad that it is finally ended. You are now free to sing again, As-she-we-qua. Please help me today to call to the spirits of the women who lost their loved ones here. Ask them to call with me to their warriors and braves, and to help me lead them from this place. Ask them to walk with me and guide me as I walk this trail. Walk with me, As-she-we-qua, until you and your people take your final journey home. Ah-ho.

(Key Terms: Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, Black Sparrow Hawk, Black Hawk, 1767, Saukenuk, Pyesa, Rock Island, Black Hawk’s Watch Tower, Black Hawk State Historic Site, Hauberg Museum, Sauk, Sac, Meskwaki, Fox, Rock River, Sinnissippi River, Mississippi River, War of 1812, British Band, Great Britain, Treaty of 1804, Treaties, Ceded Land, William Henry Harrison, Quashquame, Keokuk, Fort Armstrong, Samuel Whiteside, Black Hawk War of 1832, Black Hawk Conflict, Scalp, Great Sauk Trail, Black Hawk Trail, Prophetstown, Wabokieshiek, White Cloud, The Winnebago Prophet, Ne-o-po-pe, Dixon’s Ferry, Isaiah Stillman, The Battle of Stillman’s Run, Old Man’s Creek, Sycamore Creek, Abraham Lincoln, Chief Shabbona, Felix St. Vrain, Lake Koshkonong, Fort Koshkonong, Fort Atkinson, Henry Atkinson, Andrew Jackson, Lewis Cass, Winfield Scott, Chief Black Wolf, Henry Dodge, James Henry, White Crow, Rock River Rapids, The Four Lakes, Battle of Wisconsin Heights, Benjamin Franklin Smith, Wisconsin River, Kickapoo River, Soldier’s Grove, Steamboat Warrior, Steamship Warrior, Fort Crawford, Battle of Bad Axe, Bad Axe Massacre, Joseph M. Street, Antoine LeClaire, Native American, Indian, Michigan Territory, Indiana Territory, Louisiana Territory, Osage, Souix, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Ho-Chunk)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.