May 18, 2014

Black Hawk Island

Victory, WI

High in the branches of a hickory tree, a pair of stern, golden eyes watches the familiar landscape as the blackness of night inexorably gives way to the first blurring hints of gray in the eastern sky. The North Star hangs high above the horizon, still bright in the sky, unaware of its unique relationship to the earth. Not far away, the great Mississippi River flows almost silently along its course, unrelenting and powerful. Ducks fly by in small groups, their wings whistling in the still air as they pass. Swirls of mist begin to rise off the river, gathering like risen spirits suddenly unafraid of the coming dawn, joining ranks until they form an unbroken white doppelganger of the river below.

The eyes blink once, and the watcher’s head swivels to the right. There is unfamiliar movement and noise in the early dawn. Near the riverbank, there are people moving and splashing around, chopping down trees, and calling urgently to one another. The people are a great disturbance to the area. Many of the birds and animals that would normally be there have flown or walked away. The forest is in a state of unrest.

Suddenly a movement below catches the watcher’s eyes. A field mouse has left the safety of its underground den and hunts among the grasses for something to eat. Dropping silently from the tree, the Great Horned Owl crashes down upon the mouse with its black talons, and flies heavily away to savor its prey in a tree beyond the disquieting influence of the people.

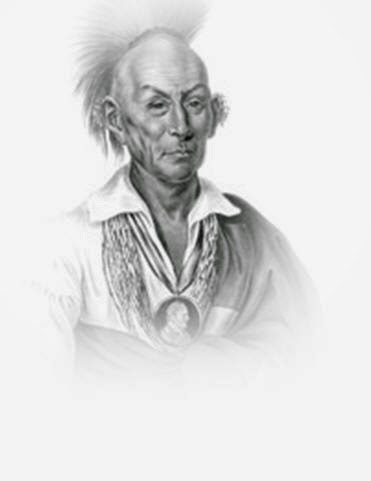

After four months of hellish discomfort, persecution, torture and deprivation, the number of survivors in Black Hawk’s Band now numbered less than 500, in whose number Black Hawk himself could no longer be counted. Only hours earlier, Black Hawk had ridden with his family away from the river, back up the trail from which they had approached, and fled to the north. Wabokieshiek, The Prophet, had taken a more direct route north along the river with his family, intent on joining Black Hawk and Chokepachepaho, Little Stabbing Chief, further upriver. Only a handful of people had traveled with them.

Black Hawk’s departure was not well accepted by those who had followed him over 500 miles of intentionally rugged and foreboding landscape. When Black Hawk left, he told his people to cross the Mississippi if they wished, and if they could, and that they should then go south to meet up with Keokuk near their former home in Saukenuk. He told them he was going to seek refuge with the Chippewa to the north, or possibly hide near the headwaters of the Ouisconsin River. Regardless of his intent, and his final words of direction for his followers, his departure left the band in a state of chaos.

Though their stated intention was to cross the Mississippi at first light, an act that would possibly have saved many lives, many survivors instead lingered well past dawn in an encampment about a mile east of the island from which they had been driven the night before by cannon and musket fire. They had no way of knowing how far away the Steam Boat Warrior had gone, or indeed why it had left at all, and a river crossing no doubt seemed even more dangerous than before. Had they known that the Warrior was still several hours away, having gone all the way to Prairie du Chien to refuel, they almost certainly would have been feverishly building rafts and canoes at the first hint of daylight. Many did, but many others hid anxiously in the otherwise inviting and peaceful location now known forever as Battle Hollow.

By 6 o’clock in the morning, the first sounds of gunfire could be heard, soft and muffled, several miles up the valley. Though there were leaders and chiefs among them, there had been no time to come to a consensus on whom to follow. Some chose to immediately chance the river, but some chose the way of the deer, standing silently so as to become invisible against the background of the forest. They knew of the plan Black Hawk and The Prophet had put in action, with the strongest and most able of the warriors to act as a rear guard, and lead the attacking army away and to the north. This sacrifice was supposed to have given them time to build their rafts and escape across the river, but fear and indecision had frozen many to the spot. Just as many of the soldiers had only first encountered and fought with the Indians here at the Mississippi, so too had many of the Indians first faced the horrors of deadly guns and cannon fire only hours before. The enemy had finally caught up to them. They were surrounded.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

It wasn’t long before General Atkinson began to suspect he had fallen for a trap. All the time as he advanced through the woods he expected to encounter the main force of the Native warriors, but when they got within sight of the river and saw only forty or fifty Indians below, he immediately sent word via his Adjutant William Bradford back to General Henry, who had not yet caught up to the main force, to take his 400 militia and follow the main trail of the Indians. Though starting an hour behind Atkinson and having been intentionally posted as the rear battalion, Henry’s troops now found themselves once again at the forefront of the pursuit, and when they reached the edge of a steep ravine, first caught sight of the fugitives in the valley below.

I have stood in the valley hollow where death swept down from the hills like a nightmare in the daytime. I have gazed up at the hillsides and watched the leaves and the branches sway, as though tossed by the passing of a long-ago memory. I have listened to the haunted wails of children echoing in my mind and wept as the scenes of murder play before my eyes in this lush and verdant landscape.

The first 200 of Henry’s troops catapulted themselves down the hillside and into battle hollow, where some Indians ran in terror for the river a mile away, and some tried to hide from the advancing men and horses. Within minutes, the true face of the upcoming horror began to reveal itself.

When Henry’s militia arrived, accompanied by Captain Dickson and his spies, they began the indiscriminate slaughter of every man woman and child in their path. Suddenly, with the fierce brutality of a trapped wolf, the Indians turned and fought back.

Black Hawk stated in his Autobiography, “Our braves, but few in number, finding that the enemy paid no regard to age or sex, and seeing that they were murdering helpless women and little children, determined to fight until they were killed!”

The remaining braves, with what few warriors remained among them, started the heaviest fighting of the entire conflict, battling hand-to-hand and tree-to-tree, giving ground only when blood and death demanded it. At the sound of gunfire, the rest of Henry’s troops poured in over the hillside to engage in the fighting. Blue smoke from the muskets began to fill the trees, adding to the chaos and placing a hazy veil over the gruesome scenes of the battle. An estimated 300 Natives, mostly women and children, were on the hillside when the attack started, and the warriors and braves paid for their escape with their lives. Time and again the soldiers advanced, and both sides suffered heavy casualties, though it was the Sauk and Meskwaki, outnumbered and starving, who could not hope to survive and their losses were severe. At length, the Indians were driven down to the river bottom, where an unrestrained frenzy of killing tainted the river red with blood.

It would be impossible for me to describe, in a linear timeline, the events that took place over the next three hours. It involves the actions of nearly 2000 people, spread out over several miles and several hours, and their intentions, motivations, loyalties and perspectives led to wildly different accounts.

The first 200 of Henry’s troops catapulted themselves down the hillside and into battle hollow, where some Indians ran in terror for the river a mile away, and some tried to hide from the advancing men and horses. Within minutes, the true face of the upcoming horror began to reveal itself.

When Henry’s militia arrived, accompanied by Captain Dickson and his spies, they began the indiscriminate slaughter of every man woman and child in their path. Suddenly, with the fierce brutality of a trapped wolf, the Indians turned and fought back.

Black Hawk stated in his Autobiography, “Our braves, but few in number, finding that the enemy paid no regard to age or sex, and seeing that they were murdering helpless women and little children, determined to fight until they were killed!”

The remaining braves, with what few warriors remained among them, started the heaviest fighting of the entire conflict, battling hand-to-hand and tree-to-tree, giving ground only when blood and death demanded it. At the sound of gunfire, the rest of Henry’s troops poured in over the hillside to engage in the fighting. Blue smoke from the muskets began to fill the trees, adding to the chaos and placing a hazy veil over the gruesome scenes of the battle. An estimated 300 Natives, mostly women and children, were on the hillside when the attack started, and the warriors and braves paid for their escape with their lives. Time and again the soldiers advanced, and both sides suffered heavy casualties, though it was the Sauk and Meskwaki, outnumbered and starving, who could not hope to survive and their losses were severe. At length, the Indians were driven down to the river bottom, where an unrestrained frenzy of killing tainted the river red with blood.

In brief, the Indians were driven to the water’s edge, where they continued to fight, attempted to hide, tried to cross to one of the main islands or one of several willow islands, or made for the opposite shore.

Henry’s troops were soon joined by the rest of the soldiers and militia, and the slaughter continued uninterrupted, until the military was joined on the river by the Steam Ship Warrior, back from a fourteen-hour round trip to Prairie du Chien. In the end, not more than 150 of the fugitive band survived the massacre.

The Battle of Bad Axe has been condemned through time as a brutal massacre of helpless women and children, carried out by soldiers acting under orders of President Andrew Jackson. Jackson’s Indian Removal Policy was the slippery slope that led to the sanctioned murder of Black Hawk’s people. Here is the entire speech, as presented to Congress in 1830.

President Andrew Jackson's Message to Congress

"On Indian Removal" (1830)

It gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly thirty years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation. Two important tribes have accepted the provision made for their removal at the last session of Congress, and it is believed that their example will induce the remaining tribes also to seek the same obvious advantages.

The consequences of a speedy removal will be important to the United States, to individual States, and to the Indians themselves. The pecuniary advantages which it promises to the Government are the least of its recommendations. It puts an end to all possible danger of collision between the authorities of the General and State Governments on account of the Indians. It will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters. By opening the whole territory between Tennessee on the north and Louisiana on the south to the settlement of the whites it will incalculably strengthen the southwestern frontier and render the adjacent States strong enough to repel future invasions without remote aid. It will relieve the whole State of Mississippi and the western part of Alabama of Indian occupancy, and enable those States to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power. It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.

What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization and religion?

The present policy of the Government is but a continuation of the same progressive change by a milder process. The tribes which occupied the countries now constituting the Eastern States were annihilated or have melted away to make room for the whites. The waves of population and civilization are rolling to the westward, and we now propose to acquire the countries occupied by the red men of the South and West by a fair exchange, and, at the expense of the United States, to send them to land where their existence may be prolonged and perhaps made perpetual. Doubtless it will be painful to leave the graves of their fathers; but what do they more than our ancestors did or than our children are now doing? To better their condition in an unknown land our forefathers left all that was dear in earthly objects. Our children by thousands yearly leave the land of their birth to seek new homes in distant regions. Does Humanity weep at these painful separations from everything, animate and inanimate, with which the young heart has become entwined? Far from it. It is rather a source of joy that our country affords scope where our young population may range unconstrained in body or in mind, developing the power and facilities of man in their highest perfection. These remove hundreds and almost thousands of miles at their own expense, purchase the lands they occupy, and support themselves at their new homes from the moment of their arrival. Can it be cruel in this Government when, by events which it can not control, the Indian is made discontented in his ancient home to purchase his lands, to give him a new and extensive territory, to pay the expense of his removal, and support him a year in his new abode? How many thousands of our own people would gladly embrace the opportunity of removing to the West on such conditions! If the offers made to the Indians were extended to them, they would be hailed with gratitude and joy.

And is it supposed that the wandering savage has a stronger attachment to his home than the settled, civilized Christian? Is it more afflicting to him to leave the graves of his fathers than it is to our brothers and children? Rightly considered, the policy of the General Government toward the red man is not only liberal, but generous. He is unwilling to submit to the laws of the States and mingle with their population. To save him from this alternative, or perhaps utter annihilation, the General Government kindly offers him a new home, and proposes to pay the whole expense of his removal and settlement.

In the last few sentences President Jackson makes clear that Indians not accepting of relocation face the possibility of total annihilation. This speech was presented to Congress in support of an Act brought forth by Jackson himself, known as the Indian Removal Act. It did not receive universal support. On April 24, 1830, the Act passed the Senate by a vote of 28 to 19. On May 16th of that year, the Act barely passed the Congress by a vote of 101 to 97. Two days later it was signed into Law by President Jackson, giving fuel for confabulated ‘Wars’ like the Black Hawk Conflict. This Act gave the President the authority to ‘negotiate’ with Native American tribes for the purchase of their sovereign lands, forcing the complete removal and relocation of all tribe members to “Indian Territories” in the west.

The most famous and tragic example of the results of this ‘voluntary’ Act was the Cherokee Trail of Tears, which resulted in the deaths of thousands of Indians. It is no surprise that for the Native Americans, Jackson is one of the most hated and vilified of all the US Presidents.

If this seemed an unusual and lengthy diversion from the main subject of this post, it’s because I have spent so little time talking about the role that this Law played in the conflict. It is important to understand, however, that the actions carried out by the soldiers and militia at the edge of the Mississippi River over these two days were not an aberration of authority, or the misguided acts of a handful of leaders. It was a sanctioned slaughter, supported at the highest levels of government, and the fate of any band of Indians who dared to defend themselves or their territory against the illegal encroachment of settlers was nothing short of an extermination order.

All of this leads me back to a more detailed description of the battle itself. As I mentioned, a linear timeline would be impossible, given the number of people, the duration, and the distances involved, and in discussing these things, a linear timeline would be meaningless. Instead, I will offer to you a composite of some of the stories that came from this day, mostly told by the soldiers who fought there. I would dearly love to include stories told from the Indian perspective, but history, as they say, is told by the living, and very few Indians survived that day to tell their side of the story. Only by reading these stories is it possible to begin to understand the ‘truth’ of what happened. It starts with a synopsis of the reflections of Phillip St. George Cooke, who took part in the events:

As Cooke describes, it is not possible for any one person to see, or to know, all that occurs in such a circumstance. This explains the bewildering differences between the accounts that have survived through time.

“General Henry had this morning been put in the rear, but he did not remain there long. Major Ewing sent his Adjutant back to General Henry, informing him that he was on the main trail. Major Ewing, at the same time, formed his men in order of battle, and awaited the arrival of the brigade, which marched up in quick time. When they came up, General Henry had his men formed as soon as possible for action.” – Major John A. Wakefield

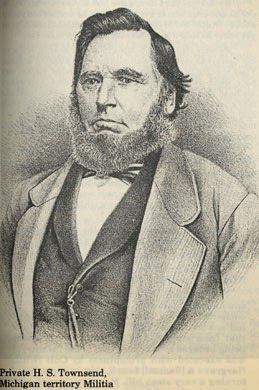

“He [Captain Joseph Dickson] was wounded in the ankle. It was said that he shot a squaw who fell on her knees before him begging for her life.” - H. S. Townsend

“When we came upon the squaws and children, they raised a scream and cry loud enough to affect the stoutest man upon earth. If they had shown themselves, they would have come off much better, but fear prevented them; and in their retreat, trying to hide from us, many of them were killed; but contrary to the wish of every man, as neither officer nor private intended to have spilt the blood of those squaws and children.” - Major John A Wakefield

“All the aged pioneers with whom I have conversed speak of this so called Battle of Bad Axe as a cruel butchery of women and children.” Dr. C.V. Porter

“A little Indian boy concealed in the driftwood jumped from his hiding place and ran for his life. Dickson ordered [Abadiah] Rittenhouse to shoot the child.

“The brave soldier raised his gun, but lowered it, saying, ‘Captain, I can’t shoot a child’!

“Dickson thereupon cursed him and said, ‘nits breed lice’, and again ordered him to kill the boy.

“He again raised his gun, but dropped it and said, ‘I tell you Captain I can’t shoot that child’.

“Just then a big Dutchman [“Big tooth” John House] came up and Dickson ordered him to shoot the poor boy. He did so and sent a bullet through his heart.

“Presently another jumped from the driftwood and the Dutchman took aim and blew the top of his head off.” - Dr. C. V. Porter

“During the battle, a Sac mother took her infant child, and fastened it to a large piece of cottonwood bark, consigning it to the treacherous waves rather than to captivity. The current carried the child near the bank, when [John] House cooly loaded his rifle, and taking deliberate aim, shot the babe dead. Being reproached for his hardened cruelty, he grimly replied, ‘Kill the nits, and you’ll have no lice.’” – William Henry Perrin, History of Crawford and Clark Counties, Illinois

In case you wonder what happened to our soldier of conscience, Mr. Rittenhouse, here is another story about the same man.

“Abadiah Rittenhouse, a spy, had a ball through his whiskers and one through the rim of his hat. He was dazed and wild after that. A squaw with a child on her back was near him. He said, ‘See me kill that damn squaw.’ He killed the squaw, and the bullet broke the child’s arm.

Private Townsend made many remarks, written and oral, including the claim that no inhumanities were visited upon the Indians that day. Yet of the intentionally killed woman and child, he simply remarked,

“When we came up, the child was gnawing on a horse bone.” - H. S. Townsend

I find it necessary at this point to interject how absurd I find this portrayal of the scene where the neatly uniformed soldier is reaching tenderly for the Indian child, lying over the naked corpse of its mother. To be sure, many of the band were reduced to rags or nakedness at this point, but the artist has portrayed both mother and child as plump and healthy, rather than the skeletal wraiths they were, and also conveniently omitted the fact that the child’s arm had been severed above the elbow and was dangling from a ragged flap of skin.

The various retellings of this event go on to say that after the fighting had subsided, the boy, roughly four years old, was taken to the makeshift surgical area, and was given a piece of dry bread. The child chewed eagerly on the bread, and was far more engaged in relieving its hunger than in the fact that Dr. Philleo finished the job of hacking off the child’s arm.

To complete the portrayal of just how the general public felt about Indian children as a whole, the local newspaper, the Galenian, for whom Philleo was an Editor, later reported, “It was soon ascertained that the arm must come off, and the operation was performed without drawing a tear or a shriek. The child was eating a piece of hard biscuit during the operation. It was brought to Prairie du Chien, and we learn that it has nearly recovered.”

It. “It” has nearly recovered. Not, ‘he’, not ‘the child’, - “it”.

“When we were at last ordered to advance, we threw ourselves down the high bluff [Battle Bluff], which was not quite perpendicular; and in the act of descending, I saw the Indians below, scampering through the woods, and occasionally firing.” – Lt Phillip St. George Cooke

“At length, after descending a bluff, almost perpendicular, we entered a bottom thickly and heavily wooded, with much underbrush and fallen timber, and overgrown with rank weeds and grass, plunged through a bayou of stagnant water, the men as usual holding up their guns and cartridge boxes, and in a few minutes heard the yells of the enemy, closed with them, and the action commenced.” – Smith, Wisconsin State Historical Society Collections

“One incident occurred during the battle that came under my observation, which I must not omit to relate. An old Indian brave, and his five sons, all of whom I had seen on the prairie and knew, had taken a stand behind a prostrate log, in a little ravine mid-way up the bluff; from whence they fired upon the regulars with deadly aim. The old man loaded the guns as fast as his sons discharged them, and at each shot a man fell. They knew they could not expect quarter, and they sold their lives as dear as possible; making the best show of fight, and held their ground the firmest of any of the Indians. But they could never withstand the men under Dodge, for as the volunteers poured over the bluff, they each shot a man, and in return, each of the braves was shot down and scalped by the wild volunteers, who out with their knives and cutting two parallel gashes down their backs, would strip the skin from the quivering flesh, to make razor straps of. In this manner I saw the old brave and his five sons treated, and afterwards had a piece of their hide.” – John H. Fonda, Wisconsin State Historical Society Collections

“Wishita, a fine looking man, & a chief of considerable standing, was wounded while crossing the Mississippi, but he, with great exertion, reached the western shore. Here the bank being steep, she [his sister] tried to get him out but could not succeed, & was obliged to leave him behind her on account of her company, which was already in advance of her. She had crossed the river on a pony, carrying her child, about a year old, before her. They hurried on, fearing an attack of our army, or an attack of the Sioux, as they were now in their country.” – John W. Spencer

“The Indians fought desperately until they were forced to plunge into the River. Many were killed in the water. Some was fortunate enough to reach the shore.” – James J Justice

“The spies killed 19 Indians before we got to the river.” – H. S. Townsend

“General Dodge’s squadron and the U.S. troops soon came into action and with Gen. Henry’s men, rushed into the strong defiles of the enemy, killed all in their way, except a few who succeeded in swimming a slough of the Mississippi 150 yards wide.” – Dr. Addison Philleo

“The regular Troops, and Dodge at the head of his Battallion soon came up and joined in the action followed by part of Posey’s Troops, when the enemy was driven still further through the bottom to several small willow Islands successively where much execution was done.” – General Henry Atkinson

“With Henry’s men we killed in three-fourths of a mile, 82 Indians. We lost three men. Indians were thick there.” H. S. Townsend

“Three squaws were shot on that race: they were naked.” – H. S. Townsend

“Capt Wells & Clark of Leach regt captured 4 Indian youths, & Capt Wilson of Hargrave regt captured 3 Squaws and four youths.” – General Henry Atkinson

“Those not killed got into the river. Henry’s men were below on island and killed those who flated down.” – H. S. Townsend

“When the Indians were driven to the Banks of the Mississippi, some hundreds of men, women and children plunged into the river, and hoped by diving, &c. to escape the bullets of our guns; very few, however, escaped our sharpshooters.” – Dr. Addison Philleo

“… during the fight the river was full of Indian ponies with women and children clinging to them. Lindsay saw six persons hanging onto one pony. Many children were supposed to have been drowned.” – Dr. C. V. Porter

“Many of the Men Women & children fled to the river & endeavored to escape by swimming in this situation our troops arrived on the bank and threw in a heavy fire which killed great numbers, unfortunately some women & children which was much deplored by the soldiers…” – Albert Sidney Johnston

“Then the Indians, charged upon with the bayonet, fell back upon their main force. The battle now became general; the Indians fought with desperate valor, but were furiously assailed by the volunteers with their bayonets, cutting many of the Indians to pieces and driving the rest to the river.” – History of Hancock County, Illinois

“The Inds. were pushed literally into the Mississippi, the current of which was at one time perceptibly tinged with the blood of the Indians who were shot on its margin & in the stream. Many passed a small Slue into an Island, where they made a stand for a while, only prolonging the action a few hours as few of them escaped.” – Joseph M. Street

“Was heavy fighting there. Squaws came to us holding up their arms. We pushed them back and killed none of them. We killed everything that didn’t surrender.” – H. S. Townsend

“And now, above the incessant roar of small arms, we hear booming over the waters, the discharge of artillery; and lo! The steamer Warrior came dashing on!” – Phillip St. George Cooke

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Warrior, fresh from its fueling run to Prairie Du Chien, arrived several hours later than its original intent, having been delayed by the morning fog over the Mississippi River. The forty-one soldiers and crew on the boat were as surprised to see the army and militia as those on shore were to see the steam boat. Neither knew that the other would be there, but together they formed a pincer maneuver that had a devastating effect on the survivors who were trying to escape.

A small number of the Indians had managed to elude the attacking army by swimming to a small series of what were referred to as ‘willow islands’, so named because willows are all that can grow on them, and they are frequently washed away by the vagaries of the river. When the Warrior arrived, they immediately began firing their cannon into these small islands, followed by gunfire. This final advantage over the Indians was an absolute death blow. The soldiers, who might otherwise have been partially thwarted by the Mississippi River as they had been at the Wisconsin River, could suddenly ride across the river on the steamboat, and power their way from island to island in search of any Indians who remained hidden. The soldiers on the steamship also had a unique and commanding viewpoint over those who tried to escape by floating or swimming away, and the slaughter continued unabated, indiscriminate of age or gender.

When Zachary Taylor and his 150 men were transported to one of the larger islands, they scoured it clean, killing all but one who had hidden there. Two of them were shot from trees.“Large numbers [of Indians] had evidently just left it [the island]; but we found only two men, whom the cannonade had driven into the branches of large trees. Instantly without orders, the volunteers commenced firing, and a hundred guns were discharged at them; I saw them drop from limb to limb – poor fellows – like squirrels; or like the Indian in ‘Last of the Mohicans’.” – Phillip St. George Cooke

When Zachary Taylor and his 150 men were transported to one of the larger islands, they scoured it clean, killing all but one who had hidden there. Two of them were shot from trees.“Large numbers [of Indians] had evidently just left it [the island]; but we found only two men, whom the cannonade had driven into the branches of large trees. Instantly without orders, the volunteers commenced firing, and a hundred guns were discharged at them; I saw them drop from limb to limb – poor fellows – like squirrels; or like the Indian in ‘Last of the Mohicans’.” – Phillip St. George Cooke

I find it bewilderingly odd that these soldiers, with their hatred of Indians so clearly expressed by their actions, thinking them to be savage animals and beasts – demons in human form – could nonetheless be so aggrieved at the loss of a single Indian by the name of As-kai-ah. As-kai-ah, also known as Ska-ah, was a Menominee Indian who happened to have been traveling with the soldiers, and fighting against the Sauk. By virtue of pointing his gun in one direction instead of another, this Menominee Indian was treated with the utmost respect by his companions. When the two Indians were shot from the trees, Askaiah leapt forward to claim the scalps, and was mistaken for one of the Sauk Indians and shot in the back.

A small number of the Indians had managed to elude the attacking army by swimming to a small series of what were referred to as ‘willow islands’, so named because willows are all that can grow on them, and they are frequently washed away by the vagaries of the river. When the Warrior arrived, they immediately began firing their cannon into these small islands, followed by gunfire. This final advantage over the Indians was an absolute death blow. The soldiers, who might otherwise have been partially thwarted by the Mississippi River as they had been at the Wisconsin River, could suddenly ride across the river on the steamboat, and power their way from island to island in search of any Indians who remained hidden. The soldiers on the steamship also had a unique and commanding viewpoint over those who tried to escape by floating or swimming away, and the slaughter continued unabated, indiscriminate of age or gender.

I find it bewilderingly odd that these soldiers, with their hatred of Indians so clearly expressed by their actions, thinking them to be savage animals and beasts – demons in human form – could nonetheless be so aggrieved at the loss of a single Indian by the name of As-kai-ah. As-kai-ah, also known as Ska-ah, was a Menominee Indian who happened to have been traveling with the soldiers, and fighting against the Sauk. By virtue of pointing his gun in one direction instead of another, this Menominee Indian was treated with the utmost respect by his companions. When the two Indians were shot from the trees, Askaiah leapt forward to claim the scalps, and was mistaken for one of the Sauk Indians and shot in the back.

“Very unfortunate one Menominee was killed in the action by a white-man by mistake.” – Joseph M. Street

“A fine young Menominee, who was by my side, ran forward, tomahawk upraised, to obtain the Indian honor of first striking the dead – I lost sight of him; - a few minutes after I saw him stretched upon the earth; - he had been shot in the back by a militia friend! It was hard to realize; a moment before he was all life and animation, burning with hope and ambition; now there he lay with face to heaven, with no wound visible, - a noble form, and smiling countenance – and but a clod of the earth!” – Phillip St. George Cooke

Why, I have to wonder, did no one pause to consider that the Indians they were in the process of murdering by the hundreds were also full of life and animation, burning with their own hopes and ambitions? What was it that made them nits and lice, when the Menominee Indian at their side was deemed a ‘fine young’ fellow?

The fighting continued among the islands, with the Warrior providing transport for the troops and a place to hold prisoners, when the soldiers could be bothered to take any. It was out here on the islands that the horrible scene of the wounded Indian boy was repeated so exactly as to appear the same incident, had not one of them taken place out here on the islands and the other on shore.

“Taylor and his men charged through the islands to the right and left, but they only took a few prisoners; mostly women and children. I landed with the troops, and was moving along the shore to the north, when a little Indian boy, with one of his arms shot most off, came out of the bushes and made signs for something to eat. He seemed perfectly indifferent to pain, and only sensible of hunger, for when I carried the little naked fellow aboard, someone gave him a piece of hard bread, and he stood and ate it, with the wounded arm dangling by the torn flesh; and so he remained until the arm was taken off.” - John H. Fonda

In a letter written by Joseph Street to William Clark on August 3rd, Street wrote, “of the fate of Black Hawk we are not able to gain any positive accounts. I rather apprehend he has escaped and is yet living.”

And what of Black Hawk? Only his Autobiography tells of his activities during this timeframe. He stated that early in the morning of August 2nd, a young brave caught up to him and his small party, bringing news. From this brave, Black Hawk learned that earlier still, when his people were first encountered by Henry, Dickson and their commands, his people attempted to surrender, but were completely ignored, and instead slaughtered where they stood.

Black Hawk stated that his intention was to return and fight with his people, and he mentions that at some point, while hiding in a thicket, a party of whites came very close by but failed to notice them. The rest of his description seems to indicate that he got close enough to the fighting to encounter at least one more of his braves, who shared with him more stories of the massacre. “After hearing this sorrowful news,” Black Hawk states, “I started, with my little party, to the Winnebago village at Prairie La Cross.”

* * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * *

There was no escape, even for those that managed to survive the harrowing crossing of the Mississippi River. Two days after the massacre, a party of about one hundred Sioux Warriors, led by Wabasha, plus a few Menominees, was given permission to pursue the fugitives who made their way across into the swamps and thickets west of the river. Within two days they returned, bringing in 22 Sauk prisoners and bearing the scalps of sixty-eight more, mostly women and children. Very few escapees ever returned to their homeland.

How many were killed? I have done a great deal of reading, and there are many estimates. I have also spent a great deal of time thinking about this post, and the information that needed to be shared in here to make the story complete. Then I realized that coming up with an answer – the exact number of Native Americans slaughtered in this unjustifiable military action – would only serve to minimize the individual human tragedy involved. It would bring an awful truth to the idea put forth by Josef Stalin; ‘The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of thousands is a statistic.’

I cannot put a name to every Native American that was killed during this two-day battle and the aftermath that surrounded it – it would be the first such accounting in written history – but if I could I would write everything I know about every one of them. Every life that was lost belonged to an individual, animated and sacred of their own right, with hopes and dreams, friends, families and loved ones. There were warriors, and hunters, and elders, and women, and young brides, and children and infants. There were widows who had lost their husbands in the recent fighting. There were mothers who had lost children. Children who had lost their parents, and were orphaned, starving and terrified of what would happen to them. Only months before, these people were living meaningful lives, facing as a community the terrible hardships placed upon them by the advancing whites, but still finding ways to struggle and survive, each of them a meaningful and productive member of their society. Every one of these people deserves to be thought of as an individual, not just collectively rolled into a large number and buried, nameless, in a mass gravesite in our memories.

So how many were killed? In a very real sense – all of them. I’m not saying that every Indian there was put to death, but even the survivors, who had suffered the complete loss of everything meaningful to them in life, mourned and wished for nothing more than a quick and easy death.

“The Warrior carried down to the Prairie [du Chien], after the fight, the regular troops, wounded men and prisoners; among the latter was an old Sauk Indian, who attempted to destroy himself, by pounding his own head with a rock, much to the amusement of the soldiers.” - John H. Fonda

I try to imagine how I would have reacted if, as a child, all of my closest friends and playmates had been shot or stabbed, and then scalped possibly while they were not yet quite dead, all within my eyesight. I try to imagine what it would have been like to see my mother’s head blown apart, or to see her fall with a bullet in her chest. I try to imaging being a mother who had two of her children starve to death during the long flight, and another child drown trying to cross the river, my husband killed or captured, and myself a prisoner of the enemy who had done all this to me. Each time I try to imagine it, I fail utterly in the attempt. Roughly 700 mainly Sauk and Meskwaki Indians took flight from the battle of Wisconsin Heights either down the Wisconsin River or across land to wind up here at the battle of Bad Axe. Fewer than 150 survived.

“On the part of the enemy, I saw but one dead squaw and one warrior; there were, however, a large number of squaws and children taken prisoners.” – Lt. Charles Bracken.

“It can never be ascertained how many were killed in this battle; but from the best calculation that could be made, I suppose we killed about one hundred and fifty; and I think it altogether probable that as many more were drowned in the attempt to cross the river.” – John Wakefield

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Makataimeshekiakiak, the great Sauk warrior and leader rode slowly north. He was being guided by Shounk Tshunksiap to the headwaters of the La Crosse River, north of the Ho-Chunk Village at Prairie la Cross. With him were Asshewequa his wife, his two sons Nahseuskuk and Gamesett, his only surviving daughter Nauasia, his close friend Wabokieshiek and his family, Chokepachepaho and his family, and a small number of his closest followers. Though they were used to traveling in silence, the forest around them seemed filled with the emptiness of the hundreds of people who were no longer there. Even the birds fell silent as they passed, and they passed the hours accompanied only by the incessant echoes of haunted loss.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

General Henry Atkinson, in one of his final acts before being relieved of his command by General Winfield Scott, posted rewards for the capture of Black Hawk and those that followed him. Prisoners were questioned, and for most of a month the soldiers and allied Indians from the Menominee, Sioux and Ho-Chunk nations searched in vain for the elusive warrior.

Black Hawk had spent much of this time recuperating. After his group had been camped for a few days, they were approached by a group of friendly Ho-Chunk, including a brother of Wabokieshiek. Though sympathetic to their cause, the Ho-Chunk counseled Black Hawk to surrender himself. They told him that the army continued to hunt for him, that there was a bounty for his capture, and he would never be safe. In the end, Black Hawk and White Cloud agreed to surrender themselves. They returned downstream to the Ho-Chunk village led by One-Eyed Decorah, and there stayed a number of days regaining his strength while preparing to surrender. It was agreed that One-Eyed Decorah, a relative of Black Wolf who was still with them, would be allowed to ‘capture’ Black Hawk and deliver him to Joseph Street at Fort Crawford, and thus collect the reward of horses and money. On August 27th, dressed in the finest of white leathers, Black Hawk, with his eldest son Nahseuskuk, White Cloud, and fifteen others were led by One-Eyed Decorah and Chaeter into the waiting arms of the U.S. Government.

|

| Black Hawk and his eldest son, Whirling Thunder |

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

There are so many, many things I have learned on my journey – things that have changed the way I think, the way I feel, and even changed what I believe about myself.

All my life I grew up with a feeling that something bad had happened; something to do with the Indians. When I discovered what it was, and that I was personally involved, I couldn’t stop myself from learning about it. The more I learned, the more I realized that I was meant to take part in the story. Not just to read about it, but to live it. To walk the hills, and touch the rivers, and hear the whispers in the wind. I received a message that I was to follow Black Hawk and his people, and tell the story to those who would listen.

So I took this journey. I traveled for hundreds of miles, searching for the truth, so that I could share not only this story, but the even deeper meaning and importance of the events. Something terrible happened to the Native American people in this country, that has resulted in the extermination of not one but dozens of rich and vital cultures. The story of Black Hawk is just one example of many such stories. Indian nations once filled this country, from the Abenaki and Penobscot in the northeast, to the Comanche and Tonkawa in the southwest, to the Seminole and Creek in the southeast to the Ojibwa and Sioux in the northwest. Every one of these tribes – ALL of them – were forcibly removed from their lands, stripped of their dignity, enslaved or slaughtered, and legislated out of existence by the relentless westward expansion of United States settlers under the waving banner of Manifest Destiny. The treatment of Black Hawk’s people, even the horrific events of the Bad Axe Massacre, were mild compared to other accounts I have read about other conflicts in our long and bloody history of wresting this land from its former inhabitants.

And yet I am not without hope for our future, or the future of the Native American Nations that are still in existence today. There is still a path that will enable them to struggle on and survive, holding onto some part of themselves that is uniquely Native American – that part which other races can never fully comprehend.

This Weblog is not about chastising the guilty, or entertaining the curious. This story has been written in an effort to restore balance in the world. When something bad happens, there is a lingering effect that can only be countered by an intentional act of ‘good’. When something devastating occurs, especially when carried out as an intentional act of evil, the long-term effects can only be overcome by the positive energy of numerous and willful acts of good.

Though this story is heartbreaking in the telling and the hearing, there is wisdom in the knowing. By sharing this story, I am taking what was once bad and using it as an act of good, to enlighten those who are still impacted by the deep-seated feelings of animosity and distrust between Whites and the Indian Nations with whom we still share this country. Less than 200 years have passed since the events I have described, and the wounds are still fresh and bleeding in many hearts and minds.

As I said, I have been changed by this story, and what I have learned about the past. I am making changes in my life to counteract the stereotypes and degradation Indians face on a daily basis. I am treating Indians differently, and letting others know when their actions or words are harmful.

Sometimes I find others who are willing to listen to my story, and learn from it. I challenge them to do something good – anything – that can help to give positive energy back to the world, and bring balance against the seemingly endless acts of violence and hatred.

If you have been moved by this story, as I have, I encourage you to find ways to ACT. Help me to bring balance to the world. Use what you have learned here and use it for good. Pay attention to all the ways that Indian Tribes are still – TODAY – being mistreated by Whites. Learn about the Penokee Hills Mine project, that is threatening to destroy the wild rice beds of the Bad River band of the Lake Superior of Wisconsin Ojibwa. Then do something about it. Learn about the violation of treaty rights. Learn for yourself that Native American Indians are not just an ‘ethnic group’ who wants special rights. They are the remnants of sovereign nations, still recognized by the Federal Government, who have suffered incredible injustices at the hands of the European settlers.

I have a post, titled, “Ways to Help Native American People”. There I have shared a few ideas for things you can do to help right the wrongs of our past. These are just a few ideas. Please, please share yours. If you are genuine in your concern, and in your suggestions, I will happily add them to my blog. Please do what you can to bring goodness back to the Indian Nations of this country, and help them celebrate their survival, and pass on their beliefs and traditions to future generations.

Great Spirit – Father Sky – Creator – God – I know I am on this earth only a short time, and I am grateful for all that has been given to me. I have food and drink to nurture my body, I have curiosity and the gift of listening to nurture my mind, and I have beauty, and wonder to nurture my spirit.

I am grateful for Love: With Love in my heart, I have sought earnestly to discover what was good, and honest, and joyful about these people. I learned to Love them not only as a people, but as individuals. In sharing this story, I have found love in others where before there was only silence.

I am grateful for Respect: The ways of other cultures are not my ways. I have used the gift of Respect to allow others to be different than I am. I have learned that the gaps that separate me from others gives each of us room to grow.

I am grateful for Bravery: My path has not always been easy. The gift of Bravery has helped me to do what is right even if others would have it differently. I see Bravery in all who face their fears and their foes with integrity.

I am grateful for Honesty: I used the gift of Honesty to tell this story as fairly and openly as I could. I reflected upon my own thoughts and motivations with Honesty, and have seen the darkness which I must change, so that I can continue to grow. When I have given Honesty to others, I have received Honesty in return.

I am grateful for Humility: I have used the gift of Humility to open myself and my mind to others; to hear what they have to say and recognize the value in every living creature. I am of the earth, and the earth will claim me. I am not better than the rocks and waters of the earth – they are my brothers and sisters. There is no end to what they can teach me.

I am grateful for Truth: With all of my heart, I have searched for Truth. The knowledge I have gained is that Truth cannot be shared in words. I have heard and read many words which do not always agree with one another. Truth is what remains when you take away all the words and feel what’s left behind. The gift of Truth is in the knowing.

I am grateful for Wisdom: Knowledge, and even Truth, are of little use without Wisdom. I have used the gift of Wisdom to discriminate between that which I know and that which I believe. When the two are in conflict, I have learned to accept what I know, and change what I believe.

Great Spirit – I have walked many miles in the footsteps of The People, to learn the lessons that at first seemed hidden yet are there for all to see. Their pain has been my pain. Their suffering has been my suffering. Their story – has become my story.

Please Great Spirit, help me to use this knowledge – this truth – this wisdom – this gift – to ease the suffering of those who yet feel the pain. When their spirits gather to dance in celebration of their lives, welcome them in your embrace.

Help me to reach out to the good peoples of the world – of all colors – of all nations – and share this message of peace. Our story does not lie in the past, but beats within our hearts and guides our minds and our tongues. Until we shed ourselves of the hatred and distrust of others, we cannot heal the perpetual scarring of our souls. It is time to love. It is time to share. It is time to dance.

This world can yet be a place of beauty and wonder, as seen through the eyes of a child. Before your children are all gone from this world, let it be so...let it be so.

Ah-ho.

(Key Terms: Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, Black Sparrow Hawk, Black Hawk, 1767, Saukenuk, Pyesa, Rock Island, Black Hawk’s Watch Tower, Black Hawk State Historic Site, Hauberg Museum, Sauk, Sac, Meskwaki, Fox, Rock River, Sinnissippi River, Mississippi River, War of 1812, British Band, Great Britain, Treaty of 1804, Treaties, Ceded Land, William Henry Harrison, Quashquame, Keokuk, Fort Armstrong, Samuel Whiteside, Black Hawk War of 1832, Black Hawk Conflict, Scalp, Great Sauk Trail, Black Hawk Trail, Prophetstown, Wabokieshiek, White Cloud, The Winnebago Prophet, Ne-o-po-pe, Dixon’s Ferry, Isaiah Stillman, The Battle of Stillman’s Run, Old Man’s Creek, Sycamore Creek, Abraham Lincoln, Chief Shabbona, Felix St. Vrain, Lake Koshkonong, Fort Koshkonong, Fort Atkinson, Henry Atkinson, Andrew Jackson, Lewis Cass, Winfield Scott, Chief Black Wolf, Henry Dodge, James Henry, White Crow, Rock River Rapids, The Four Lakes, Battle of Wisconsin Heights, Benjamin Franklin Smith, Wisconsin River, Kickapoo River, Soldier’s Grove, Steamboat Warrior, Steamship Warrior, Fort Crawford, Battle of Bad Axe, Bad Axe Massacre, Joseph M. Street, Antoine LeClaire, Native American, Indian, Michigan Territory, Indiana Territory, Louisiana Territory, Osage, Souix, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Ho-Chunk)